A traditional Japanese snack

Japan is a snackers' heaven. Convenience stores are everywhere you look, and hot and cold running snacks are at your fingertips 24 hours a day.

Potato chips alone come in well over 100 flavors, running the gamut from exotic Thai tom yum and Caesar salad to the more Japanese-inspired gyoza (pork dumpling) and mentaiko (spicy cod roe).

Just as varied in style and flavor is a more traditional snack - sembei, aka the Japanese rice cracker. You can find sembei flavored with soy sauce, nori (dried laver seaweed), kombu (kelp), sesame seeds (both black and white), and soybeans, plus a huge range of more modern flavors like cheese, chocolate, and kimchee.

Smaller sembei often come mixed with other snackable ingredients such as peanuts or pine nuts.

Sembei variations

Traditional sembei are large, round and savory. Another type is arare (literallly "hailstones") - tiny and usually pellet-shaped, but also found shaped like animals (like the tanuki, or badger), seeds, maple leaves (momiji) or cherry blossoms (sakura).

A third type is kaki - bite-sized and sold in a variety of shapes. Sembei aren't all savory either; sweet sembei are made with wheat flour instead of rice flour.

One unusual variation is yasai sembei, vegetables that have been thinly sliced, covered in sugar and baked. Nuresembei are rice crackers that have been heavily doused with soy sauce and mirin, leaving a mochi mochi (chewy) consistency.

Look for genkotsu if you want something extremely hard, or try zarame (sugar-coated sembei) if you've got a sweet tooth. And a Tokyo shop called Mame Gen sells a popular snack made from nuts and beans covered with a sembei-like coating.

There are strong regional variations as well - sembei from Kanto (the area around Tokyo) were originally based on uruchimai, a non-glutinous rice, and they tend to be more crunchy (kari kari) and richly flavored.

On the other hand, sembei from Kansai (Kyoto/ Osaka) were made from glutinous rice, and they're more lightly seasoned and delicate in texture (saku saku).

Sembei have a long history, going back to the ninth century in Japan and even further back to the seventh century in China. The original crackers were sweet and flour-based, and it wasn't until the 17th century that rice was used. If you want to step back into time,

Finding sembei

Asakusa is one of the best places to observe the final step in the sembei-making process - the grilling and seasoning of the crackers. There are a few vendors along the route leading up to Senso-ji Temple where you can get sembei hot off the grill for around 100 yen.

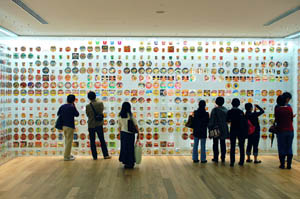

If you'd like to sample a larger variety of sembei, head over to your closest department store food floor (depachika). You should be able to find it all there - savory and sweet, in various shapes and flavors. And different textures too: ranging from kari kari to saku saku to the unusual mochi mochi, you should be able to find just the right level of crunch for you.

How sembei are made:

Rice flour is mixed with hot water and kneaded.

The dough is rolled into balls and then steamed.

The dough is kneaded once more and rolled into large coils.

At this point, any integrated flavorings (like nori or sesame seeds) are added (but not soy sauce, which is added at the very end).

The flavored dough is rolled out into thin sheets and then cut into shapes, traditionally circular.

The cut dough is then laid out on straw mats to dry in the sun.

The final step is grilling the crackers and then seasoning them with a soy sauce and mirin blend, which is brushed on.

Photos:

1. Typical round sembei

2. Mixed kaki sembei

3. Arare sembei with pine nuts

4. Traditional sembei shop in Tsukishima, Tokyo

5. Department-store sembei counter in Kobe

More cuisine articles

- © Copyright Lobster Enterprises

- Privacy

- Bento.com top

- © Copyright Lobster Enterprises

- Privacy

- Bento.com top

- © Copyright Lobster Enterprises

- Privacy

- Bento.com top